Gifford Cheesman at Building 1510, Yongsan Garrison

A Story of an English man on Yongsan Garrison

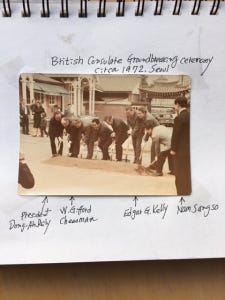

Article Submitted by Nam Sangso.

Gifford Cheesman, a native of Surrey, England, first came to Korea with his father in 1931. He was 23 years old. His father was a gold miner in the current North Korea. Gifford joined Seoul Club in 1932 as a founding member, then returned to England. And came back to Korea after the Korean War was over and received the Foreign Registration Card of South Korea. His ID card showed the Korea’s Serial Number #1. He was an eager member of the Masonic Lodge.

He joined Trans-Asia Engineering Associates, Inc. in mid 1960s as an administrator when the American architect/engineering firm was located in the Building 1510 in the Main Post, U.S. Army Yongsan Garrison.

Being a typical British gentleman, Cheesman spoke accented British English. He uttered often “jolly” for very good or great, but didn’t say “bloody.” He was a man of courteous, decent and fair, and took pride in his British sense of humor. An umbrella was often seen standing against the wall of his office.

As his desk was next to mine and architect Kyu Lee (the last prince of Korea who was born and grown in Japan) we have had good times conversing each different stories and cultures of the United Kingdom, Japan and Korea. The English people arriving in Seoul sought to meet Cheesman first as he was an easy dictionary of Korean cultures for the new comers. High ranking U.S. and U.N. Officers at Yongsan Garrison had too enjoyed to meet with Cheesman as he knew so many things of not only South Korea but also North Korea as he had been in the mineral rich northern Korea while his father was looking for gold deposits there.

Having had a gold miner father, Gifford too had kept a dream of finding a bonanza one day. While I was assigned at the Trans-Asia’s Saigon office in 1965 ~ 68, Gifford was persuaded, more like deceived, by some Korean gold diggers that there is an abandoned gold mine by Japanese in Seongwhan village some 20 km south of K-6/Camp Humphrey. The old mine was called Yulgeum (Chestnut) Gold Mine. Cheesman thought his dream of becoming rich by hitting a vein of chestnut size gold has finally arrived and persuaded the directors of Trans-Asia Engineers to finance his newly establish company, Yulgeum Mining Company. Cheesman believed that Japanese gold diggers had to return home in the middle of the tunnel digging, just before reaching the vein, when Japan surrendered the Pacific War.

When I returned to Seoul from Saigon in October 1968, the CEO of Trans-Asia Engineers asked me to check on Cheesman’s gold mine venture as the engineering company’s small safe is showing the bottom as the cash continuously flows into just the tunnel digging, without any trace of gold. I didn’t like the name of Chestnut Gold Mine which smelled fraudulent. I quickly researched at the libraries on the gold mine business Japanese had left in Korea. My conclusion was that there was almost no chance of meeting gold vein in South Korea although there had been several gold mines attempted by Japanese.

Crude oil, coal or nonmetallic minerals from the earth are fully consumed and do not leave much wastes on the surface. In the case of gold digging, the grade is an average of one gram per ton of ore body provided if one hits the seam of the gold ore. Yulgeum mine was a hard rock, encased in quartz vein, and it must be extracted from the rock rather than picking up fragments in loose sediment like a placer mining does.

Cheesman, poorly dressed, was staying in a shack he built near the entrance to the tunnel holding a magnifying glass checking every batch of broken rocks out of the tunnel. The diggers are paid by hourly rate, and relying on their guessing work to determine the direction of the tunneling was too risky, I noticed immediately. I reported to the board that the wandering about in the dark tunnel must be stopped now, and the CEO accepted my recommendation. But Cheesman insisted that the company had already spent a huge amount of money and demanded to continue to dig. He believed chestnut sized golds must be there, somewhere, to be found.

I pointed out this is just like the Concorde fallacy, and I strongly insisted to stop digging. It was decided to stop digging but still some company officers couldn’t abandon lingering attachment to a bonanza dream.

In the field, I locked the pithead with an iron gate and fired everyone. Then mobilized bulldozer and graded acres of gentle hills, and planted pear saplings (Seongwhan county is famous for farming fine pears)

In the dimly lit tunnel surrounded by rocks I was hopeless. But now I could see the saplings grow well under the bright sunlight. Years later when the land had successfully become as an orchard, Trans-Asia Engineers sold, as I suggested, the pear orchard along with the gold mine license and has recovered not only the money poured into the tunnel but with a bonanza of profit. Pear above ground was better than chestnut size gold in the ground.

Some 50 years of the time have passed. On the occasion of Chuseok Day last week, I went to Cheesman’s grave, plot H-19, at Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul. Gifford Cheesman died in February 1985 at the age of 77.

“My dear Mr. Cheesman, do you still believe we should have continued digging toward the chestnut size golds hiding somewhere in the tunnel? Actually, I can’t tell who was right, you or I,” I mumbled holding the gold digger’s grave stone which has "So mote it be" been engraved.

Your good friend, Nam Sang-so (sangsonam@gmail.com), September 2018

Do you think he was related to Ashley Cheeseman who lives in Korea now and is a chef and university professor?